Land records are created when a person acquires land, either from the government or from another person. The first time land was transferred from the government to an individual is called a grant and results in a patent. Every subsequent sale of that same land to another individual results in a record called a deed. Because land records were kept from the time the first settlers arrived in a new area, they are some of the earliest records that might exist for our ancestors. The most obvious information contained in a land record is where a person lived and when he lived there. While the amount of obvious, genealogically significant information contained in land records might be minimal, many valuable details could be included in land records that will provide clues about relationships, economic standing, occupation, military service, or immigration status.

State-Land vs. Federal-Land States

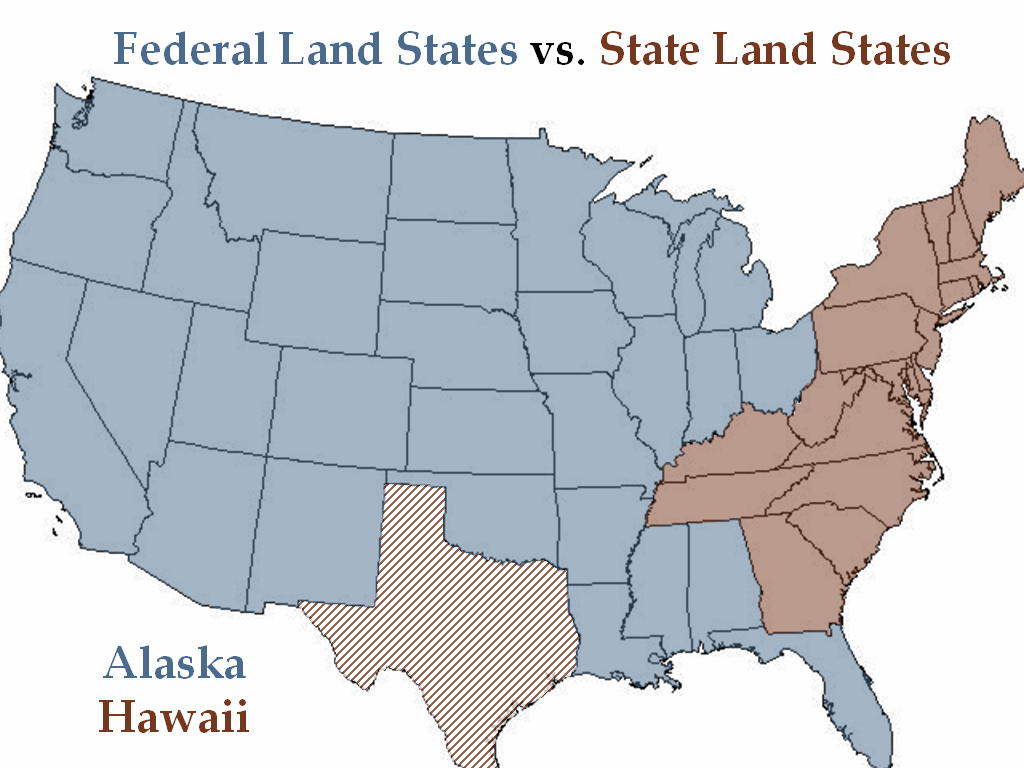

Twenty states retained control of the distribution of land when they became a part of the United States. They are known as state-land states. In the remaining states, the federal government was in charge of disbursing land. They are known as federal-land states. The map below shows which states belong to which group:

Because my accreditation region is the Mid-Atlantic region (including the states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland), my current focus is on state-land states. In this blog post, I will review the process for the initial and subsequent transfer of land in these states, talk about how land was measured in state-land states, and then talk about how to find land records. For additional information about federal-land states, visit the FamilySearch Research Wiki or read this article by Diana Elder at FamilyLocket.

Land Grants in State-Land States

There were basically five steps in the land grant process in state-land states. [1]

- The person seeking the grant filed an entry, or application, which was a request for land, usually a certain amount in a particular place.

- After the entry was approved, a warrant was issued. A warrant was a written order to survey the land. The warrant was usually issued to the applicant, who then presented it to the office where the warrant was to be carried out.

- A survey was then conducted. This was the process of measuring and marking the land and drawing a tract diagram or plat.

- A license was then issued. This was a document that gave the applicant permission to inhabit the land. In some states this was known as a return of survey. It signified that the purchase price and all fees had been paid.

- A patent, or the final deed from the proprietor or the state passing ownership of the particular tract of land to its initial purchaser, was then issued.

This process originated during colonial times. After the Revolution, state-land states did not turn their land over to the federal government, and the process continued unchanged from the end of the Revolution forward.

Additional Types of Land Transfers in the Colonies

Another type of grant was known as a headright grant. This was a grant given by the colonies to persons who paid the passage for settlers to come from the Old World to the colonies, and was used to increase settlement in the New World.

Additionally, simple cash sales also took place in some instances. Wealthy individuals or companies would buy large tracts of land and lease the land to others. Many of these landowners remained in England and collected rents from their tenants. In colonies established under proprietary grants (which include Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania), the lord proprietors collected annual rents through their agents. These agents created and maintained two copies of what were known as rent rolls. One copy was retained in the county and a duplicate was sent to the lord proprietor. During the revolution, most states seized the proprietary lands and sold them.

Subsequent Land Transactions

When one of the original owners sold their land to a buyer, the resulting document was a deed. A land deed may include the following information: [2]

Genealogically significant information:

- Family names and relationships.

- First name of the wife.

- The first deed in a new place may mention the previous location of residence.

- If a person has moved, the deed for their previous property may tell the new location of residence.

- Deeds often give the names of adjacent property owners, who might be family members.

- Land was often given to soldiers or their widows for military service.

The legal portions of a land deed include the following:

- Date of the land sale, date of recording, and date of verification

- Names of the grantor (seller) and grantee (buyer)

- Granting clause, specifying the interest being transferred and consideration (money)

- Property description (legal land description)

- Recital clause, if present, states how the seller got the land

- Warranty section, stating how the seller will be liable to the buyer in case of later problems

- Execution Section containing acknowledgments, seals, and signatures

Land Measurement in State-Land States

State-land states measured distances using a system of metes and bounds. The metes and bounds system is described as follows:

Distance was usually measured with an instrument called a Gunter’s chain, measuring four poles (sixty-six feet) in length and consisting of 100 linked pieces of iron or steel. Indicators hung at certain points to mark important subdivisions. Most metes and bounds land descriptions describe distance in terms of these chains, or in measurements of poles, rods, or perches – interchangeable units of measurement equaling 16 1/2 feet, or 25 links on a Gunter’s chain.

Kimberly Powell, “Metes, Bounds & Meanders: Platting the Land of Your Ancestors,” blog post, 17 March 2017, ThoughtCo. (https://www.thoughtco.com/metes-bounds-and-meanders-ancestral-land-1420631 : accessed 3 June 2021).

Here are a few common terms used in this system: [3]

- Acre: 43,650 square feet, 160 square rods.

- Chain: 66 feet, 22 yards, or 4 rods (100 links).

- Furlong: 660 feet or 220 yards (10 chains).

- Link: 7.92 inches. There are 25 links in a rod and 100 links (or 4 rods) in a chain.

- Mile: 5280 feet (80 chains, 320 rods, or 8 furlongs)

- Perch: 5 1/2 yards or 16 1/2 feet; also called rod or pole.

- Pole: 5 1/2 yards or 16 1/2 feet; also called perch or rod.

- Rod: 5 1/2 yards or 16 1/2 feet; also called pole or perch.

- Rood: As a measurement of length this varies from 5 1/2 yards (rod) to 8 yards, depending on locality. It was also used sometimes to describe area, being equal to one-quarter acre.

Platting your ancestor’s land, or drawing it onto paper just as a surveyor would have done, has several benefits for genealogists:

- Determine whether the amount of land being sold is the same amount that was originally purchased. If not, that will be a clue that you should look for additional land records.

- Identify neighbors to add to the ancestor’s FAN club, leading to additional records that might provide clues about your ancestor’s life.

- Help distinguish men of the same name from one another.

To learn how to plat your ancestor’s land, read this article by Kimberly Powell.

How to Find Land Records

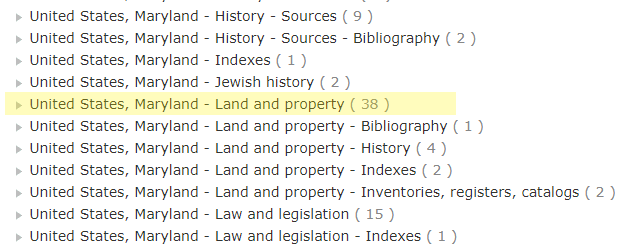

The FamilySearch catalog is a great place to begin your search for land records. Conduct a place search for the state first. After searching for the state, scroll down the list of record types to “Land and Property.” Click on this heading and a list of records applicable to the state will open. These could include colonial records, proprietary papers, land grants, and more.

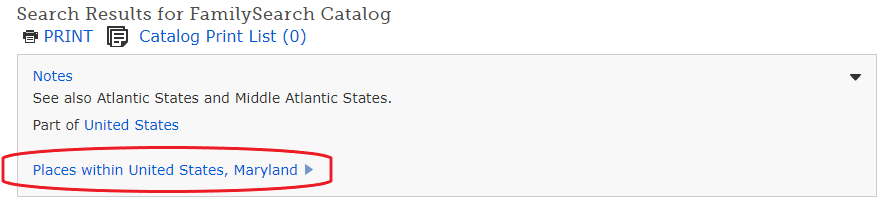

After learning what is available on the state level, drill down by county by going to the top of the state list and clicking the “places within [state]” link.

Select the county of interest from the list that opens, then scroll down and select “Land and Property.” All resources held by FamilySearch for that county will show on this list and you can select what type of records you want to look at. Each county will have its own system for indexing the records. Some have index books for the entire collection, others have an index at the front of each book. For an explanation of the Russell Key Index system used in some collections, read my article Pennsylvania Land Records: Deeds here.

Although many land records are available at FamilySearch, that is not the only place to find land records. To learn where additional records might be held, visit the FamilySearch Research Wiki page for your state and click on “Land and Property Records.” For example, the Maryland Land and Property page refers researchers to the Maryland Land Records site, a collaborative resource provided by the Maryland Judiciary, the 24 elected Court Clerks of Maryland, and the Maryland State Archives to “provide free online access to all verified land record instruments in Maryland.” Users need simply register for an account to access the records.

I hope these tips will help you understand and learn how to use land records more effectively in your research. In my next post, I will share some land records that have been valuable in some of my own research projects.

[1] Val D. Greenwood, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy, 4th ed. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2017), 471-72. [2] “United States Deeds,” FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/United_States_Deeds : accessed 4 June 2021). [3] Val D. Greenwood, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy, 4th ed. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2017), 502.