Welcome to the fourth installment in a six-part series about evidence analysis, or the process by which we determine the reliability of the evidence we discover in our research. Part One discussed the value of evidence analysis and presented three important questions to ask ourselves as we examine historical records about our ancestors:

- When and how was the source created?

- Who provided the information for the source?

- Do the facts in the source directly or indirectly answer the research question?

Part Two addressed the first question, “When and how was the source created?” Part Three helped us answer the second question, “Who provided the information for the source?” Today, we will look at the third question, “Do the facts in the source directly or indirectly answer the research question?”

Three Classes of Evidence

Evidence is defined as “our interpretation of information we consider relevant to the issue being investigated.”1 Evidence is classified by whether or not it provides a direct answer to a research question. It can be classified in one of three ways:

- Direct Evidence: If the evidence contained within a historical document provides a direct answer to a research question, it is classified as direct evidence. For example, if your question is “When was my ancestor born?” and a record provides the research subject’s exact birth date, then it provides direct evidence for the answer to your question. It is important to note that just because a record provides direct evidence, that doesn’t always mean it provides a CORRECT answer. Sometimes direct evidence is inaccurate.

- Indirect Evidence: If the evidence contained in a historical document provides a clue about the answer to your research question without directly answering the question, that is considered indirect evidence. Two or more pieces of indirect evidence must be combined to form a conclusion. For example, the 1850 census provides the names of all people in a household, but does not state their relationships. A man, woman, and children of the correct ages with the same surnames and all living in the same household in 1850 are likely to be a family. However, the census alone is not sufficient to prove those relationships. Perhaps the woman might be a sister to the man. Maybe some of the children are nieces and nephews. Additional information is needed to correlate with the census data before a conclusion can be made.

- Negative Evidence: Sometimes, you expect that a certain condition will show up in a record. When it doesn’t, that is negative evidence for something. Let’s say your research subject should have been a seventeen-year-old in her father’s household in 1880. When she isn’t listed as a member of that household, that is negative evidence that she either died before 1880, got married, or was living elsewhere for some reason.

Let’s use an analogy to help understand the three types of evidence better. A few summers ago, my husband and I needed to do some repair work on our sprinkler system. If you are unfamiliar with automatic sprinkler systems, let me explain the basics of how they work. Water is piped to a valve box through the main line, a PVC pipe that is buried beneath the lawn. The valve box is the control center for the sprinkler system, housing the valves responsible for regulating the flow of water to different zones. These valve boxes are also buried underground with their cover at ground level for ease of access.

Within the valve box, you’ll find several valves, each controlling a specific zone of the sprinkler system. These valves are electronically operated and are connected to a central control unit, often located in the garage or utility room of the property. When it’s time for a particular zone to be watered, the control unit sends a signal to the corresponding valve, instructing it to open.

Once the valve for a specific zone is opened, water is allowed to flow into the underground pipes connected to that zone. These pipes are fitted with sprinkler heads strategically placed throughout the landscape. As water pressure builds within the pipes, it eventually reaches the sprinkler heads, causing them to pop up and distribute water across the designated area.

As part of our repair task, we needed to identify which valves controlled which sprinklers in our backyard. Because the pipes were buried, we needed to do some detective work to figure this out. As we worked on this, it struck me that this was the perfect analogy for direct, indirect, and negative evidence.

Direct Evidence

Sprinkler installers plan out the system, then dig trenches in the ground and lay PVC pipe from one place to another. Then they glue everything together before burying the pipes. Before the pipes are buried, you can see exactly which pipes go from a valve to the sprinklers in the yard. Because you can clearly see the path, you have direct evidence for which valve controls which sprinklers.

Indirect Evidence

Once the pipes are all buried and the lawn is in place, you can no longer see the paths for each pipe. When you open the valve box, it is difficult to predict exactly where the pipes from each valve go, so you have to use more than one piece of information to answer the question of where the pipes go from a particular valve. The first step is to turn on one of the valves. The second step is to see which sprinklers come on. Because you turned on the valve and water came out of certain sprinklers, you have indirect evidence that the pipes from those particular valves feed certain sprinklers. You can’t clearly see the path, but the evidence is every bit as compelling. When you turn on Valve A, water comes out of sprinklers 1-5. Your conclusion is very reliable.

Negative Evidence

If you turn on valve A and sprinklers 1-5 do not spray water, that is negative evidence for one of two situations: either the pipe from valve A does not go to those sprinklers, or the pipe is broken, making it so the water doesn’t make it to sprinklers 1-5. You expected that if the valve controlled that zone and the pipes were intact, those sprinklers would have turned on. Because they didn’t turn on, you can form a hypothesis about what is going on. By turning on each valve, you can gather enough evidence to form a conclusion. Negative evidence can be very compelling as well.

Let’s take a look at how these principles work with historic documents.

Examples

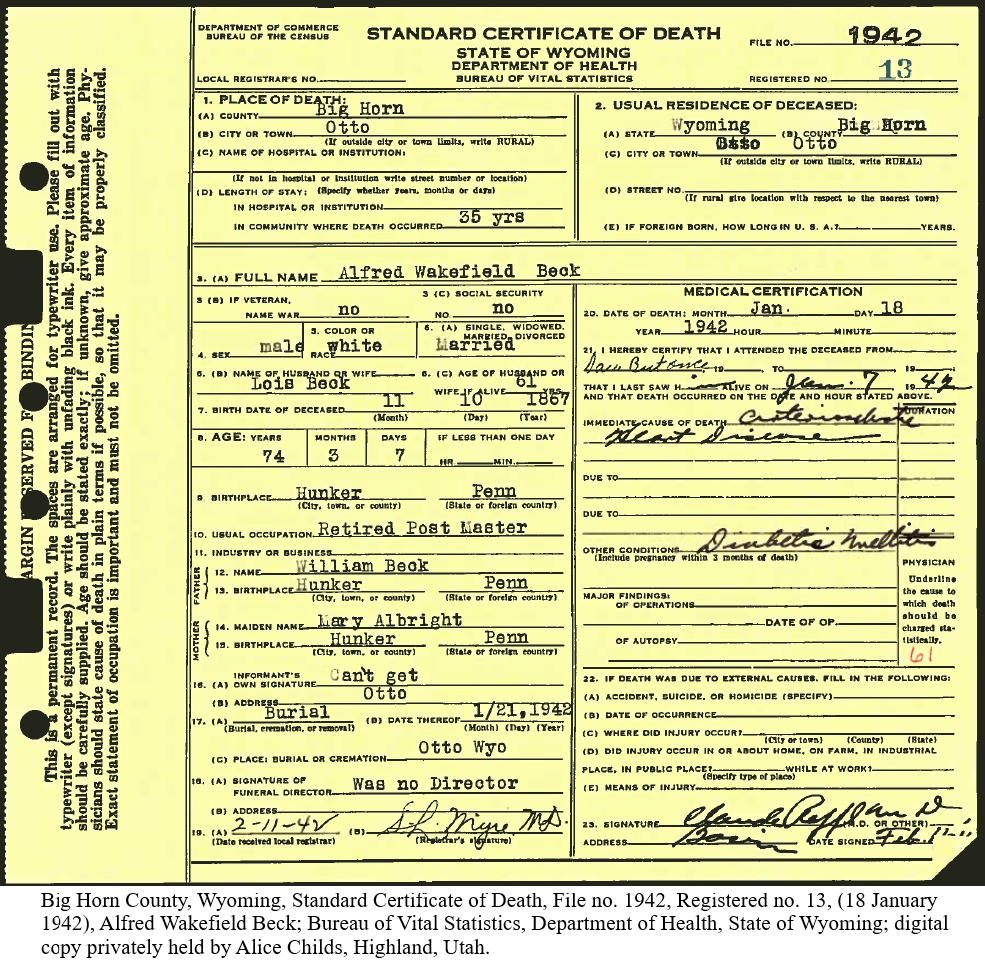

When analyzing the evidence, we must always have a research question in mind. Without a research question, what would the document provide evidence for? Let’s say our research question is “When was Alfred Wakefield Beck born? Alfred’s death certificate directly tells us that his birthdate was 10 November 1867, so it provides direct evidence for his birth date.

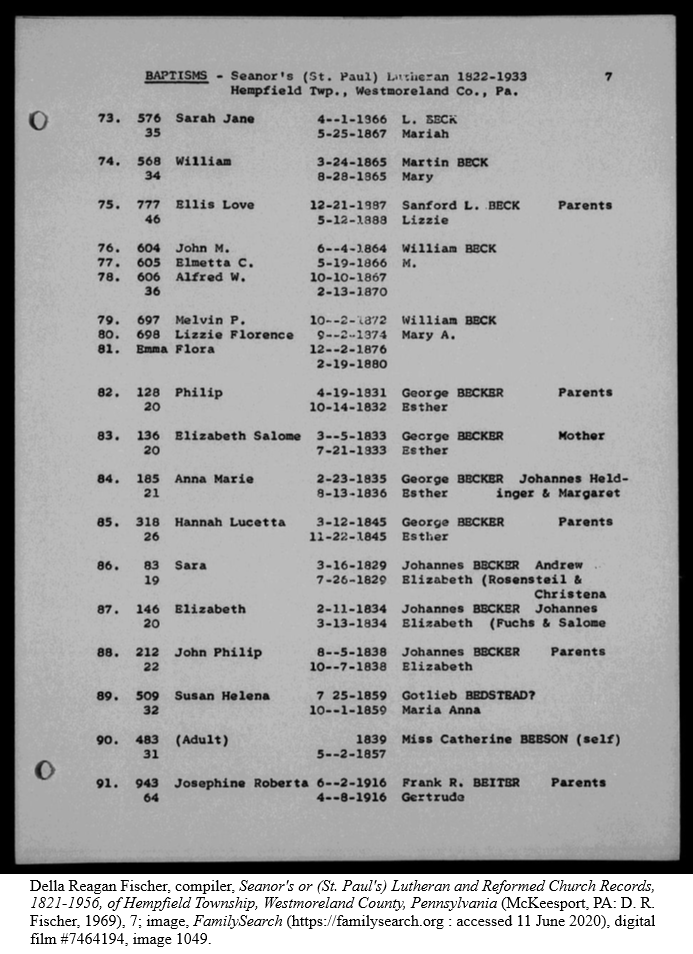

Next, let’s look at our transcribed church record. This record provides the exact birth dates for each child who was baptized on a particular day in Seanor’s Church in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. It also directly answers the research question “When was Alfred Wakefield Beck born?” However, this record states that he was born in October 10, 1867. You can see that both documents directly answer the research question but one of them has to be wrong. We will talk about resolving conflicts like this in the next blog post.

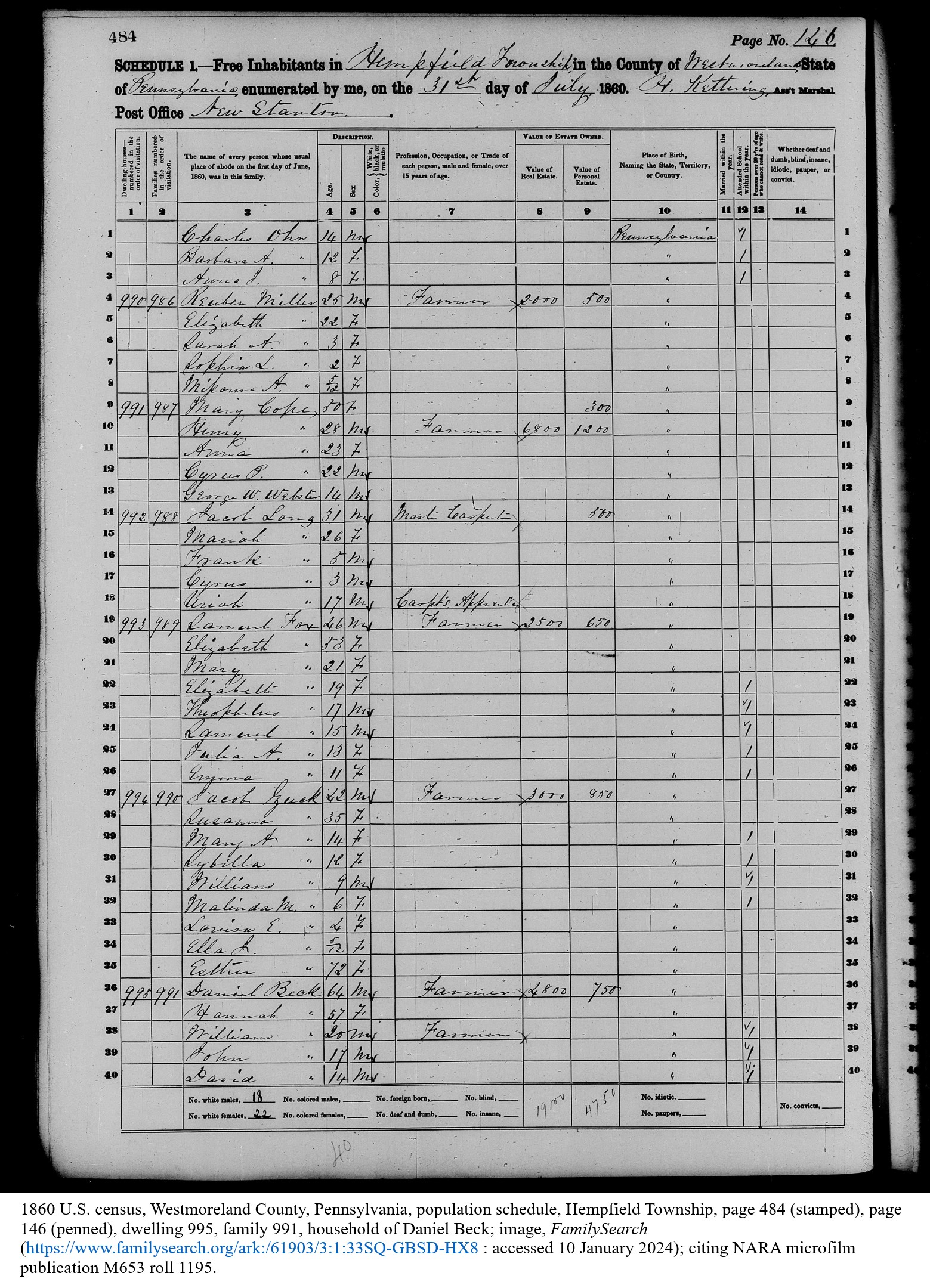

Next, let’s take a look at a census record from 1860. William Beck was a twenty-year-old who lived in the household of Daniel Beck, age sixty-four. If our question is “Who was William Beck’s mother?” we can surmise that it might have been fifty-seven-year-old Hannah, who also lived in the household. However, since relationships were not stated on this census, we can not draw this conclusion based on this record alone. Hannah was old enough that she could have been William’s grandmother. Or perhaps William was a nephew. We need more than one record to ensure we are drawing the correct conclusion.

Now let’s think about negative evidence. William had a sister named Catharine who was just three years his senior. If our research question is “When did Catharine marry?” this census would provide negative evidence that Catharine might have married before 1860 (or at least have moved out of the house by then). If she was not married, we would expect that she might have been enumerated in this household.

Summary

Evidence is the meaning you assign to the information contained in a source. This meaning comes as you ask a research question. To analyze the evidence, ask yourself, “Does the information in the record directly answer the research question?” Direct evidence provides a direct answer to the research question. Indirect and negative evidence provide clues that must be combined with evidence from other sources to answer the research question. All three types of evidence can be compelling.

In my next post, I will bring together what we have learned about sources, information, and evidence and discuss how we can use these principles to help resolve conflicts that arise in our research.