This series focuses on how I applied the steps in the Research Like a Pro process for a personal research project. I walked through these steps in a study group I participated in last fall. The first step was to create a research objective. This was mine: Trace the descendants of Robert Dale in search of potential autosomal and Y-DNA test takers. Robert was an agricultural laborer born on 30 August 1801 in Bracon Ash, Norfolk, England. Robert married Dinah Dawson on 13 October 1823 in Wreningham, Norfolk, England. He died in April 1879 in Flordon, Norfolk, England.

The next step in the process was to create a timeline to analyze what I already knew, spot holes in the research, and determine which localities I would be researching during this project. All the events in Robert and Dinah Dale’s lives took place in Norfolk County, England, so that became the subject for my locality guide.

After taking these steps, I was ready to create a research plan. The process of creating the research plan includes several steps:

- Create a Summary of Known Facts.

- Add background information that will be relevant to the research.

- Create a working hypothesis.

- Identify sources that might provide the answers to the research question.

- Prioritize the order of research.

Summary of Known Facts

The summary of known facts can be taken directly from the timeline, and depending on how much you know about the research subject, it can be written in paragraph format or if there are a lot of details, you can create a bulleted list or table. Be sure to add citations to every fact.

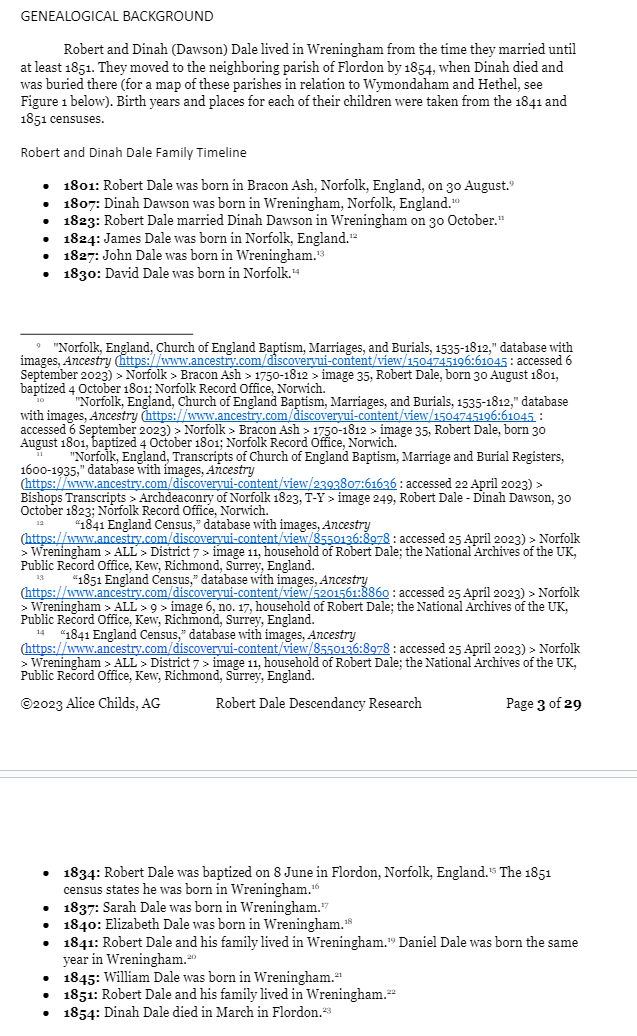

For my project, I chose to use a combination of the two, starting with a brief introductory paragraph followed by a timeline of known facts about the family:

Background Information

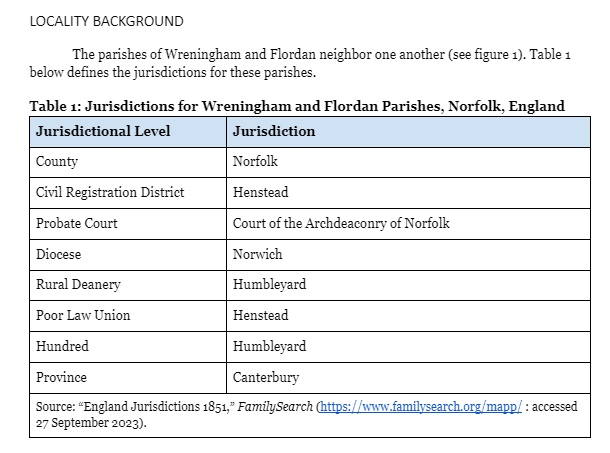

Background information will help place the family in historical context. I typically create a few paragraphs based on what I learned while creating my locality guide. For this project, I decided it would be important to remember the different jurisdictions in Norfolk, so I created a table for those:

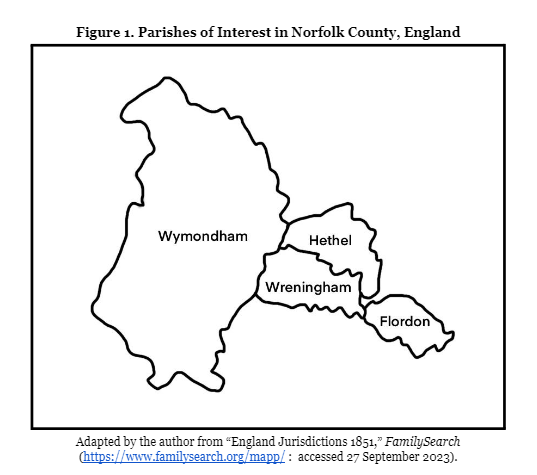

I also wanted to illustrate where the parishes of interest were in relation to one another in a simple map. I created the map using the mobile app Procreate on my iPad. This app allows you to bring in a base map and trace what you want onto a new layer with an Apple pencil. You can then save the new layer as an image.

I also wrote the following paragraphs as part of my background information:

Civil registration of vital records began in England in 1837, so vital records for each of the children in the family should be available except birth records for the eldest sons, James, John, David, and Robert. While events might still be kept in parish records, this was done less frequently, so vital records might be the best source for births, marriages, and deaths for subsequent generations. Census records through 1921 will also be valuable for tracing the families.

Migration could be a factor for the research on this family. In the decade from 1851 to 1861, almost 42,000 Norfolk residents migrated to London, and another 11,000 migrated to Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, and Essex. Migration into the more urban areas of Norfolk County like Norwich was also common.1

Not all migrants remained in urban areas after their initial migration. Sixty-eight percent of the migrants who survived to 1871 remained in London. Some, like female servants saving for a dowry for marriage, returned home to Norfolk.2

Working Hypothesis

The next step in creating the research plan is to hypothesize what the answer to the research question might be and develop a strategy or methodology for proving or disproving this hypothesis. Here is mine:

Robert and Dinah Dale’s children might have remained in Flordon and its surrounding parishes. However, they may have followed a common pattern for the time and migrated into more urban areas of Norwich or into London, Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, and Essex. If families migrated together, they will be easier to identify. Tracing the migration of single individuals and women might be difficult, especially for those with common names. Occupation, a typical identifier, was not static for migrants into urban areas from Norfolk, and women were generally under-recorded.3

Making note of key identifiers such as birth date, birthplace, and parent names and occupations will help trace the family members in censuses, vital records, and cemeteries. For later generations, probate records and newspapers might be the most beneficial record types.

List of Identified Sources

The next step in creating a research plan is to use your locality guide to make a list of sources that might help you meet your research objective. My list consisted of the following record types. I’ve simply stated what I expected I might find in each type in the list below. In my actual research plan, I included links to repositories and online collections under each record type:

- Cemetery Records – birth and death dates, possible familial connections.

- Church Records – birth, marriage, and death dates and places, names of parents, and father’s occupation.

- Immigration Records – records of family members who immigrated to the U.S.

- Living People – People-Finder websites to help locate living descendants that I could ask to take a DNA test.

- Military Records – One of the Dale sons likely served in the Royal Navy.

- Newspapers and Directories – Obituaries and other articles to help connect family members and trace their possible migration.

- Probate Records – Generational links.

- Vital Records – birth, marriage, and death dates and places, names of parents, and father’s occupation.

Prioritized Research Strategy

With a long list of possible resources to utilize, the next step is to prioritize which records are most likely to answer the research question. Those that are easily accessible will be prioritized over those that have to be requested or searched in person. At this stage, pick just a few items, and then determine what else needs to be added as you go. Below you will see my initial plan. In my research project document, I added links to every record collection for efficiency.

- Solidify the births of each child to their parents and ensure all children of the family have been discovered. Utilize church records and the England and Wales Birth Registration Index, requesting original vital records as needed.

- Trace each child as fully as possible in census records from 1851 – 1921. Identify additional generations along the way.

- Use birth, marriage, and death registration indexes to confirm generational links, requesting original vital records as needed.

On to Research!

The next step in the Research Like a Pro process is to carry out the research plan, keeping a research log along the way. My next post will outline my steps as I went through this process and how I adjusted my research plan as needed along the way.

- Roger Woods, “Mid-Nineteenth Century Migration from Norfolk to London: Migratory Patterns, Migrants’ Social Mobility, and the Impact of the Railway,” Dissertation for an MA in Historical Research, September 2014, p. 1; digital version (https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5779/1/Roger_Woods_-_Migration_from_Norfolk.pdf : accessed 28 September 2023).

- Roger Woods, “Mid-Nineteenth Century Migration from Norfolk to London: Migratory Patterns, Migrants’ Social Mobility, and the Impact of the Railway,” Dissertation for an MA in Historical Research, September 2014, p. 8; digital version (https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5779/1/Roger_Woods_-_Migration_from_Norfolk.pdf : accessed 28 September 2023).

- Roger Woods, “Mid-Nineteenth Century Migration from Norfolk to London: Migratory Patterns, Migrants’ Social Mobility, and the Impact of the Railway,” Dissertation for an MA in Historical Research, September 2014, p. 2; digital version (https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5779/1/Roger_Woods_-_Migration_from_Norfolk.pdf : accessed 28 September 2023).