Do you have immigrant ancestors? I recently completed a project that included immigration as an element. It was a fun project, and I wanted to share what I have learned about tracing immigrant ancestors. Today I will start with the most recent records that will have been created for your ancestor: naturalization records. In Part Two I will discuss ship passenger lists. Part Three will be all about finding your ancestor’s place of birth. Learning about these records and methodologies will help you discover more about the immigrants in your family history and may even help you break down some brick walls on your family tree.

What is Naturalization?

Naturalization is defined as the admittance of a foreigner to the citizenship of a country. The records created during the naturalization process can provide valuable genealogical information. In this article, I will discuss the history of naturalization, then go over the process of naturalization and describe what documents were created. Finally, I will give some tips on finding naturalization records for your ancestors.

History of Naturalization

- In the early history of the British colonies, very few citizens were naturalized.

- Prior to 1868 immigrants often merely signed a statement of allegiance as they came off the boat. Some of these “Citizenship Lists” are contained in various books.

- In 1868 the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. It guaranteed national citizenship status and extended its full benefits to everyone who was either born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction, but there was no comprehensive regulation of naturalization until 1906.

- Prior to 1906, all matters of naturalization were handled by the federal, state, and municipal courts. Most applicants went to whichever court was closest to them.

- In 1906 Congress established the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (INS) and prescribed a specific procedure to be followed.

- Between 1906 and 2003 the Bureau of Immigration and Bureau of Naturalization were split, put back together, and moved between different governmental departments.

- In 2003 the INS was abolished and its functions divided between three agencies, which were moved to the Department of Homeland Security. These agencies are the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Naturalization of immigrants is currently the responsibility of USCIS.

The Naturalization Process

For many years, naturalization was a two-step process that required at least five years to complete. After residing in the United States for at least two years, an alien was eligible to file a Declaration of Intention (also called “first papers”). The purpose of the Declaration of Intention was for an applicant to renounce allegiance to foreign governments and declare their intention to become a citizen of the United States. After three more years, the applicant could file a Petition for Naturalization. Once the petition was granted, a Certificate of Citizenship was issued. The applicant also had the right to choose people to make Depositions in support of his declaration, indicating how long the applicant had lived in a certain location and giving an appraisal of the applicant’s character.

Photo from the Library of Congress

There have been some notable exceptions to this process:

- Between 1790 and 1922, the wife of a naturalized man automatically became a citizen.

- Between 1790 and 1940, children under 21 automatically became naturalized citizens when their father was naturalized.

- Between 1824 and 1906, minor aliens who had resided in the US for at least five years before turning 23 could file both their declarations and petitions at the same time.

- An 1862 law allowed an Army veteran of any war who was honorably discharged and who had at least one year of residency could file his Petition for Naturalization without having previously filed a Declaration of Intent. An 1894 law extended the same privilege to Navy and Marine Corps veterans.

Genealogically Significant Information Found In Naturalization Records

Prior to 1906, Declarations of Intention usually contained the following information for each applicant:

- Name

- Country of birth or allegiance

- Date of the application and signature.

- Some show date and port of arrival in the United States.

After 1906, the declarations contained significantly more detail:

- Name

- Age,

- Occupation

- Personal description

- Date and place of birth

- Citizenship

- Present address

- Last foreign address

- Vessel and port of embarkation for the United States

- Port and date of arrival in the United States

- Date of the application and signature

Prior to 1906, Petitions for Naturalization may have contained the following:

- Name of the petitioner

- Sovereign to whom he is foreswearing allegiance

- Sometimes the petitioner’s residence, occupation, date and place of birth, and port and date of arrival in the United States

After 1906, petitions contained much more information:

- Name

- Residence

- Occupation

- Date and place of birth

- Citizenship

- Personal description of applicant

- Date of emigration

- Ports of embarkation and arrival

- Marital status, names, dates, places of birth and residence of applicant’s spouse and children

- Date at which U.S. residence commenced

- Time of residence in the state

- Name changes

- Signature.

After 1930, Petitions for Naturalization often include photographs of the applicants.

Was Your Ancestor a Naturalized Citizen?

Naturalization was not required. To discover clues about whether your ancestor became a citizen, the following sources can be used:

- The 1870 census (column 19) has a checkmark for “Male Citizens of the U.S. of 21 years of age and upwards.” If the person was a foreign-born citizen, this means that he had become naturalized by 1870.

- The 1900 census (column 18), the 1910 census (column 16), and the 1920 census (column 14), and 1930 census (column 23) indicate the person’s naturalization status. The answers are “Al” for alien, “Pa” for “first papers,” and “Na” for naturalized.

- The 1920 census (column 15) indicates the year in which the person was naturalized.

- When a naturalized citizen (or alien seeking naturalization) filed a homestead claim, the application included the name of the court where naturalization took place.

- Passport applications also give the name of the court where naturalization took place.

Finding Naturalization Records for Your Immigrant Ancestors

If you have determined your ancestor was a naturalized citizen, you can begin looking for the naturalization records. Records for naturalizations handled in federal courts prior to 1906 are held in the Regional National Archives. Naturalization records from county and state courts may still be at the county court, in county or state archives, or at regional archives serving several counties within a state.

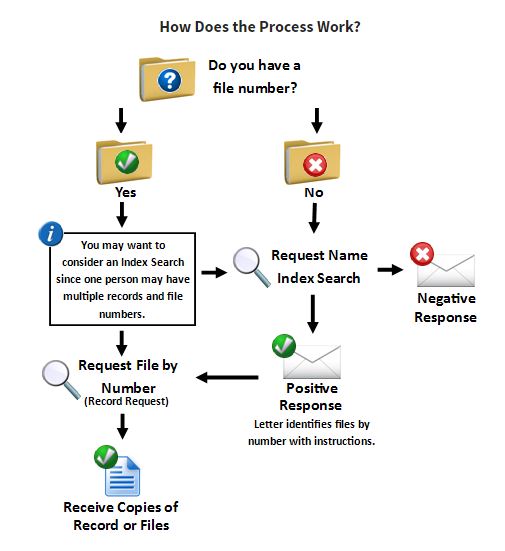

Records for naturalizations occurring after 1906 are held by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS). The process for obtaining records through USCIS is as follows:

There is a fee of $65 for an index search and an additional fee of $65 for a file request to obtain naturalization records from USCIS.

In addition, some naturalization records are digitized and indexed on various family history websites, including Ancestry, Family Search, Find My Past, and MyHeritage. However, these websites contain incomplete record collections. If you are unable to locate naturalization records for your immigrant ancestor on these sites, you may request records from the Regional National Archives or USCIS.

Because of the genealogically significant information contained in naturalization records, don’t hesitate to seek the actual records when evidence suggests that your immigrant ancestor was a naturalized citizen but you are unable to locate him or her in one of these indexed databases.

Sources:

Greenwood,Val D., The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy, 4th ed. (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2017), p. 560-567, “Citizenship and Naturalization Records.”

“Naturalization,” The National Archives (https://www.archives.gov/ : accessed 16 November 2019).

“Genealogy,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (https://www.uscis.gov/genealogy : accessed 16 November 2019).

[…] you have a chance to read the articles in my series “Tracing Your Immigrant Ancestors?” In Part 1, I explored Naturalization Records. Part 2 was all about passenger lists. Last week I published […]